The It Girl

Clara Bow, 1930

Clara Bow, 1930

I recall that it was a blustery, cold Halloween night in 1969 when we went to see The Band in concert. We'd toked up pretty good inside a friend's car, in a parking spot we'd miraculously found on Saint Stephen Street, directly behind Symphony Hall. Normally we would have taken the Red Line then the Green Line to Symphony Hall from our Beacon Hill apartment, but I guess whoever we went to the concert with had wheels, and we were happy not to have to stand outside and smoke in the cold. Second-hand smoke under these circumstances is a good thing.

The concert at Symphony Hall that night was The Band, touring behind their second album. The surprise, unbilled opening act was Van Morrison, who was living on the other side of the river in Cambridge at the time and who I don't think we'd ever heard of. I believe the ticket price was $5.00, which was a lot of money in those days, considering the fact that I was making $1.25 per hour at my job at The Book Clearing House on Boylston Street. (Gail supplemented our income with her job at Harvard Divinity School.) The monthly rent for our apartment was $100, and we were living large enough to take a two-week vacation in England that year, which included a stop at the Isle Of Wight festival. We didn't have to worry about where our next smoke would come from, and we always seemed to have a little money left over each month at Suffolk Franklin Bank. (We paid for that UK vacation in advance, in cash.) Good times indeed.

What immediately caught our attention inside Symphony Hall once we'd found our seats (stage right with an excellent view down to the stage) was the massive array of speakers and other assorted sound equipment deployed on the stage, and what are now called "sound technicians" (we called all non-band members of rock groups "roadies" or "groupies") scurrying about, communicating with the engineer at the sound board in the back of the hall, getting the sound levels just right. We had never before seen such attention to detail at a concert; we soon discovered why it was all so important, and how The Band was different from all the other live performers we had seen up to this point.

Van Morrison was introduced by Robbie Robertson, and proceeded to play very strong set, considering that he was completely blotto. A bottle of Jack Daniels sat precariously on top of one of the Marshall speakers, and I suspect alcohol was not the only agent in his system that night. As loud as the sound was - and the sound at rock concerts back then (as now) was loud - it was crisp, clear, and just about perfect (except for the slurred lyrics on Van's part). "Into The Mystic" blew our minds.

Van ended his set passed out on the stage. On the Queen's birthday in 2015, he became "Sir Van". And so it goes...

As for the Band, their set was astonishing. Every note sounded just like it did on their albums. We had never before experienced that kind of precision and absolutely perfect renderings of music that we were intimately familiar with from countless listenings on vinyl, and through reasonably good stereo speakers, given the state of home audio technology in the 1960s. (Now of course, everything sounds incredible right through the headphones attached to your phone.)

But then, we had no reason expect to hear the lyrics sung clearly and balanced with the instruments. Part of it can be attributed to the marvelous acoustics of Symphony Hall, of course, but most of it was accomplished through the sophisticated application of technology and a commitment to excellence on the part of the artists, as well as pride in this amazing body of work they had created.

It was a magical evening.

This photograph perfectly captures the state of the Boston Red Sox tonight, having coughed up a seven-run lead to the Toronto Blue Jays.

Ever since I started walking by the back lot of a towing company/body shop that receives some of the worst wrecks in Boston, I've noticed that I've been driving much more defensively.

A jazz original.

The Rolling Stones are once again on tour in the United States, filling enormous stadiums and shaking loose every dollar they missed in 2013, when they played smaller venues. In their seventies now for the most part, they still deliver high-quality rock and roll to audiences that include many people the age of their grandchildren.

I've been noticing lately that the Baby Boomer generation, of which I am a founding member, has not been receiving very much love as we "age out" of the general population. Boomers are about as popular with other generations as Tom Brady and the New England Patriots are with the population outside New England. And that's okay with me. As the tee shirt slogan of the moment in Boston asserts: "They hate us because they ain't us."

Credit: The Atlantic. Granted, this is a posed shot to generate smiles from readers who think it's exaggerated. But based on what I've seen of the demographic of the tribe that's preparing to attend the Grateful Dead Reunion this Summer, it's not far off.

This Atlantic article really got me to thinking about how my generation has always refused to comply with norms. And most of us now simply refuse to meet the expectations others have for us as we "age out" of the population. Other generations have done their share of navel-gazing, and none quite so eloquently as "The Lost Generation" as chronicled by one of its greatest writers, F. Scott Fitzgerald:

"We were born to power and intense nationalism. We did not have to stand up in a movie house and recite a child's pledge to the flag to be aware of it. We were told, individually and as a unit, that we were a race that could potentially lick ten others of any genus. This is not a nostalgic article for it has a point to make -- but we began life in post-Fauntleroy suits (often a sailor's uniform as a taunt to Spain). Jingo was the lingo.

"That America passed away somewhere between 1910 and 1920; and the fact gives my generation its uniqueness -- we are at once prewar and postwar. We were well-grown in the tense Spring of 1917, but for the most part not married and settled. The peace found us almost intact--less than five percent of my college class were killed in the war, and the colleges had a high average compared to the country as a whole. Men of our age in Europe simply do not exist. I have looked for them often, but they are twenty-five years dead.

"So we inherited two worlds -- the one of hope to which we had been bred; the one of disillusion which we had discovered early for ourselves. And that first world was growing as remote as another country, however close in time."

If Boomers are indeed hogging all the resources and oxygen in the process of perpetuating our social and (especially musical) preferences and looking out for our own self-interests, then so be it. The lessons we pulled out of the debris and rubble of the 1960s, Vietnam, Watergate, and the struggle for civil rights taught us that we needed to look out for ourselves first and foremost, while maybe doing a little good along the way. And especially to keep on rocking in the free world.

Tom Wolfe was a major part of what came to be called "The New Journalism" in the early 1960s. His prose was to conventional reporter-prose as Impressionist art was to classical art of its time, and he made anything he wrote about interesting and incandescent, especially to an undergraduate student majoring in American Literature. Later on in the 1960s, Hunter S. Thompson came along with his drug and alcohol infused essays on politics, race, rock and roll, and an America coming apart at the seams. Rolling Stone magazine was must-reading every two weeks for a large number of disaffected young citizens hungry to see what Thompson or Wolfe or one of the other young Rolling Stone staff writers would have to say about the cataclysmic events that seemed to roll through every week in that fever dream time at the end of the 1960s.

Here's an excerpt from Tom Wolfe's "Las Vegas" from Esquire Magazine in 1964, which pretty much captures him at his best:

Bugsy [Siegel] pulled into Las Vegas in 1945 with several million dollars that, after his assassination, was traced back in the general direction of gangster-financiers. Siegel put up a hotel-casino such as Las Vegas had never seen and called it the Flamingo—all Miami Modern, and the hell with piano players with garters and whatever that was all about. Everybody drove out Route 91 just to gape. Such shapes! Boomerang Modern supports, Palette Curvilinear bars, Hot Shoppe Cantilever roofs and a scalloped swimming pool. Such colors! All the new electrochemical pastels of the Florida littoral: tangerine, broiling magenta, livid pink, incarnadine, fuchsia demure, Congo ruby, methyl green, viridine, aquamarine, phenosafranine, incandescent orange, scarlet-fever purple, cyanic blue, tessellated bronze, hospital-fruit-basket orange. And such signs! Two cylinders rose at either end of the Flamingo—eight stories high and covered from top to bottom with neon rings in the shape of bubbles that fizzed all eight stories up into the desert sky all night long like an illuminated whisky-soda tumbler filled to the brim with pink champagne.

Tom Wolfe, Esquire Magazine February 1964

It's amazing to me that ten years ago, there was no iPhone and no Facebook. These days, it seems, everything has become much more immediate, and much more ephemeral.

I have been thinking a lot about this lately, and Memorial Day last month brought to mind my father's death in the military when I was a baby. That was very long ago, in another century, but it got me to remembering specific events in my life, reminding me that it's time to update the timeline I began several years ago, also in another century.

I learned from Jim Croce that you can't catch time in a bottle. But I also learned that I could create a spreadsheet, indexed by year, starting with the year I was born, and then flesh out my personal history in separate columns for things like the car I drove, where I lived and at what address, what school I was going to and what grade I was in, who in the family died that year, or had a major illness, who my significant other was - you get the idea. An Excel spreadsheet has an almost unlimited number of columns for you to drop in as much information as you require.

When I built my personal timeline, I added things like my wife's age, my kids' ages, which pets we had, where everyone worked, where we vacationed, things like that. And as more and more details accumulated, I began to get a pretty detailed and comprehensive picture of what the year 1982 (for instance) was like.

I have done quite a lot of work on ancestry.com, tracing our family heritage back more than two hundred years, and that has been an exciting process of discovery for me. But the timeline adds flavor and texture to the broader picture that Ancestry can create.

One of the things that always seemed to be lacking when I studied history in school was context. There was always a push (even more so now, I gather) to remember and be tested on discrete names, dates and events, but very little time learning what else was happening simultaneously with these things. I can re-create any specific year of my life now, with all of the detail I've layered into my timeline, and almost feel like I'm reliving it. And every visit and re-creation suggests more details.

I'm not planning to write an autobiography, but if I ever did, my timeline would be a great place to begin.

A craft beer store opened a few years ago in an upscale suburban town west of Boston. Knowing a thing or two about retail, and having once operated a bookstore in that same town, a couple doors down, I was curious about how the owners of the craft beer store were thinking about the niche they had carved out for themselves, and their business plan.

So I became a customer, got to know the owners a little, signed up for the newsletter, set up a frequent-buyer account, and over the next few months attempted to educate myself about what was actually in some of those $8 bottles of beer with the clever labels, from small breweries with ironic names that were seemingly springing up everywhere, blessed by home equity loans, angel investors, and the Gods Of Venture Capital. The various beers were said to be infused with all kinds of things, some of them aged in whiskey barrels, and all of them subjected to a wide range of other free-range processes. They were discussed in a language that reminded me in many ways of how wine is discussed and marketed. Some of the bottles I purchased were good, some were awful, but all of them were expensive, relative to what I could buy a six-pack of Samuel Adams for (or Yuengling whenever I was in Philadelphia, before they expanded their distribution into New England).

I attended a couple of "Craft Beer Expos" and chatted up a few founders and principals of craft brew start-ups, most of whom were bright young fellows who spoke passionately and knowledgeably about the manufacture, quality and particular characteristics of their beers. After a time, I noticed an "us versus them" theme emerging, pitting the upstart small craft breweries and their customers (us) against Coors, Budweiser, Miller, and the other giant breweries (them). When I inquired as to whether any of the founders/principals would be open to being acquired by one of "them" someday, the answer was "no", but I imagine that if old Adolph Coors came calling with a fistful of dollars, looking to add a "craft beer" label to his lineup of mainstream beers, they would likely rethink their position. I've noticed some of "them" already marketing new beers with clever ironic names (like Shock Top) which make them look very much like craft beers.

Something about the craft been phenomenon feels to me like a bubble. I browsed a gigantic beer selection at a Boston area Wegman's the other day, and was astonished at how much real estate craft beers occupy, relative to mass market beers. Real estate at Wegman's is not inexpensive, and they don't bequeath it to a product or a category unless that product produces profitable retail dollars. And as with all of the products they carry, Wegman's has priced the craft beer to sell.

I'm reminded of an early episode of "Mad Men", in which Sterling Cooper has landed the Heineken Beer account, at a time when imported beers were all new and shiny in the United States in the early 1960s. Don Draper developed a successful marketing campaign for Heineken that infused (sorry) the brand with status and prestige and resulted in consumers paying a premium to feature the brand at special dinners and for special occasions.

I'm going to use Wegman's beer department as a barometer to gauge the extent to which craft beer will carve out a permanent niche for itself. I'm sure there are a lot of Don Drapers out there trying to figure out how to make that happen too.

It could be worse. At least it's not Monday.

Remembering

I haven't watched him for at least twenty years, since his show was called "Late Night With David Letterman". Still, I was compelled to watch his final show the other night. A friend had posted a clip of Bob Dylan singing "The Night We Called It A Day" from earlier in the week, and had I found it a tremendously moving coda for Letterman the man, and all he had meant for all those years he was so relevant to those of us who watched him. I seriously doubt there's another person Dylan would honor like that.

I also watched the Tina Fey's #LastDressEver segment (on YouTube) because, well, Tina Fey.

I DVR'd the final show, and found it slow and unsatisfying until the video montage at the end of the show, played over the Foo Fighters performance. It was all quick-cut, but very moving, and it really underlined for me how much the show has been on autopilot for the past twenty years. The New Yorker had a very good takeaway on the finale.

I actually appeared on "The Late Show With David Letterman" in 1991, when it was still that hip-ish show that followed "The Tonight Show With Johnny Carson" on NBC at 12:30 AM, and was broadcast from 30 Rockefeller Plaza in Manhattan. The third edition of The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading And Bubblegum Book had just been published, and our publisher arranged an extensive media campaign, which included David Letterman and Larry King. Brendan had done the author tour and promotional appearances for the first edition (described eloquently in our book), and this time it was my turn.

What I most remember about that appearance is the amount of time I spent on the phone with the show's Producer in the weeks prior to my appearance. I discovered that what looks spontaneous on television may possibly be spontaneous, but usually it's the result of careful planning. The Producer really got to know me over the phone and discovered which parts of the book would be the most fun for Dave, and what themes in the book would generate the most laughs. He had read the book (I don't think Dave had) and was the person who realized in the first place that the sarcastic tone of our writing would match up well with the show. But he had to get a sense of the potential guest (me) and what I might bring to the table, and he had to make me comfortable in advance so that I wouldn't get blindsided by anything once my segment actually began. It was planned, but not scripted. It was trememdous fun.

My most lasting and clearest memory of that appearance doesn't have anything to do with my segment (which went very well), but rather with how small the studio was, and how close the audience was. And especially with that particular night's musical guests - Booker T and the MGs. They played through all the commercial breaks, as well as performing a song or two during the show. They happen to be one of my favorite groups and that was better than any big venue concert they would ever do. It was very much like a club date.

So here's to you, Dave. All the best, and thanks for everything!

.

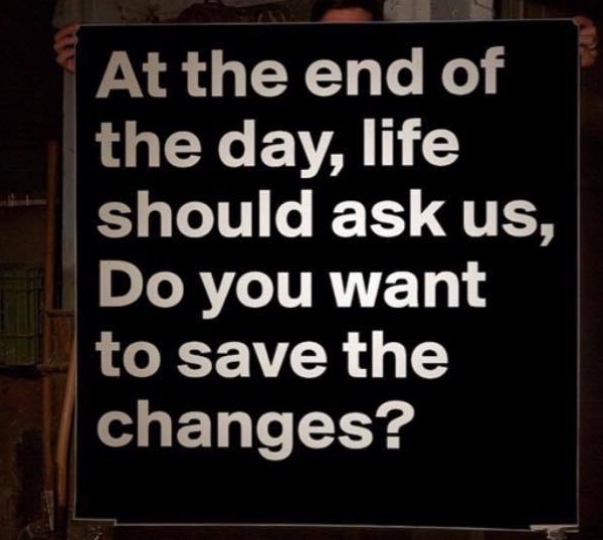

Phil Ochs, one of the most gifted singer/songwriters of his generation (and there were a lot of them in the 1960s), was so overwhelmed by changes that he took his own life. But before he did, he wrote a beautiful song about them - simply titled "Changes."

As the sign suggests, computers frequently offer do-overs, especially for writers. Regardless of what we write, I think most writers would agree that we spend a lot of time editing what we've written, which imposes a useful discipline on us when we engage in other forms of communication (especially text messages), where there's never a prompt to reconsider what we've just so heatedly typed, either for content or style. Especially for content.

But life never offers us the chance to delete the changes we've made during the day. We give them a certain amount of thought in the moment, when we make them, or as we decide whether to do or not to do something. But then they're done. And we move on, with the consequences of the changes we've made.

I honestly don't know why I'm waxing philosophical about changes today. I haven't undergone any significant transitions lately, other than creating my own website - which has allowed me some space and motivation to be writing more frequently. But as to a specific reason, I think it's probably the sign in the photograph. Sometimes, images just jump off the page at me, grab hold and stay around. That's what this one did to me. But it also brought Phil Ochs back to mind, and I wanted to be sure that people who read my writing and are not familiar with his music get to hear his "Changes."

This one's for you, Phil.

Don Draper is not real. I don't care about the real McCann Erickson guy who thought up the iconic Coke commercial, "I'd Like To Teach The World To Sing". And I'm not interested in speculating about how Don would have fought through the corporate culture at McCann to sell his concept. The ending of the Don Draper part of the series finale was just so perfectly cynical and so in character for Don, that it deserves to stand on its own. That's how that character in this story would have pushed through his darkness and gloom to re-invent himself once more at an ashram, taking out of the EST-like group therapy "seminars" those elements he needed in order to experience the breakthrough that would propel him forward.

I think that my Facebook friend Dick McDonough would especially enjoy this exhibition in at The Skirball Gallery in Los Angeles. I wish I could invent a reason to visit the Left Coast myself, just to see it. Graham was a very important figure in the production and promotion of live rock and roll concerts in San Francisco and New York in the 1960s and 1970s. The exhibition also focuses on Graham's life, as a child refugee from The Holocaust (his parents didn't make it out), and as an inspirational American success story. Business people hated him and the artists he promoted loved him. So did his customers.

I started blogging several years ago on the Blogger platform. I called my blog "Antelope Freeway" in homage to the Firesign Theatre. I took a break from blogging for a while, and now I'm back, and I'll be blogging here on my own website. Moving from Blogger to Squarespace has been like moving from the suburbs to the city. And like Peter Max, I love cities.

So all new posts, beginning with this one, will only appear here, on my website. Antelope Freeway will continue to exist at the old address, but will not receive new posts.

Last night's series finale of "Mad Men" was very satisfying for me. As someone who has watched every episode more than once, I had imagined several different ways that Don/Dick's story might have ended. But the image of Don "finding" himself at the Northern California retreat - putting himself through the hippy-dippy seminars and using his experience as a vehicle for his own self-discovery - was wonderful. That he came out of that with the concept for the iconic McCann Erickson Coca Cola ad was so perfectly cynical and so perfectly reflective of what the show has always been about that it almost brought me to tears. Well, not really. But you know what I mean.

And I love the way Matthew Weiner inserted a sneaky preview in the penultimate episode, with Don attempting to fix the motel Coke machine, of how Coke would be at the core of Don's epiphany on the mountaintop.